THE ART AND SCIENCE OF GIVING AND RECEIVING CRITICISM AT WORK

UNDERSTANDING

THE PSYCHOLOGY OF CRITICISM CAN HELP YOU GIVE BETTER FEEDBACK AND

BETTER DEAL WITH NEGATIVE REVIEWS.

And

those moments are often some of the toughest we all face in work and

life. Hearing potentially negative things about yourself is probably

not your favorite activity, and most of us would rather avoid the

awkwardness that comes with telling someone else how they could

improve.

But

what do we lose out on when we avoid these tough conversations? One

of the fundamental skills of life is being able to give and receive

advice, feedback and even criticism.

If

given and received in the right spirit, could sharing feedback—even

critical feedback—become

a different, better experience than the painful one we’re

accustomed to? Could feedback become a valued opportunity and even a

bonding,positive

experience?

In

this post, we’ll explore how to give and receive feedback at work

in the best ways possible, along with some of the psychology behind

handling critical feedback (in both directions). I’ll also share

with you some of the methods in which we offer and receive feedback

at Buffer to try and make the experience less scary and more loving.

WHAT HAPPENS IN OUR BRAINS WHEN WE RECEIVE CRITICISM

It’s

hard for us to feel like we’re wrong, and it’s even harder for us

to hear that from others. As it turns out, there’s a psychological

basis for both of these elements.

Our

brains view criticism as a threat to our survival

Because

our brains are protective of us, neuroscientists say they go out of

their way to make sure we always feel like we’re in the right—even

when we’re not.

And

when we receive criticism, our brain tries to protect us from the

threat it perceives to our place in the social order of things.

"Threats

to our standing in the eyes of others are remarkably potent

biologically, almost as those to our very survival,"

says psychologist

Daniel Goleman.

So

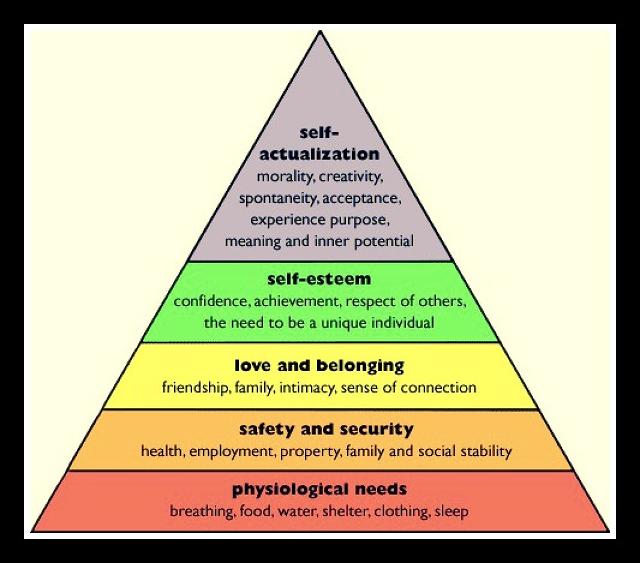

when we look at Maslow’s famous hierarchy of needs, we might

suppose that criticism is pretty high up on the pyramid—perhaps in

the self-esteem or self-actualization quadrants. But because our

brains see criticism as such a primal threat, it’s actually much

lower on the pyramid, in the belonging or safety spectrums.

Criticism

can feel like an actual threat to our survival—no wonder it’s so

tough for us to hear and offer.

We

remember criticism strongly but inaccurately

Another

unique thing about criticism is that we often don’t remember it

quite clearly.

Charles

Jacobs, author of Management

Rewired: Why Feedback Doesn’t Work,

says that when we hear information that conflicts with our

self-image, our instinct is to first change the information, rather

than ourselves.

Kathryn

Schulz,

the author of Being

Wrong,

explains that that’s because "we don’t experience, remember,

track, or retain mistakes as a feature of our inner landscape,"

so wrongness "always seems to come at us from left field."

But

although criticism is more likely to be remember incorrectly, we

don’t often forget it.

Clifford

Nass,

a professor of communication at Stanford

University,

says "almost everyone remembers negative things more

strongly and in more detail."

It’s

called a negativity

bias. Our

brains have evolved separate, more sensitive brain circuits to handle

negative information and events, and they process the bad stuff more

thoroughly than positive things. That means receiving criticism will

always have a greater impact than receiving praise.

HOW TO OFFER CRITICISM THE BEST WAY POSSIBLE

So

now that we know what a delicate enterprise criticism can be, how can

we go about offering it up in the right spirit to get the best

results? Here are some tips and strategies.

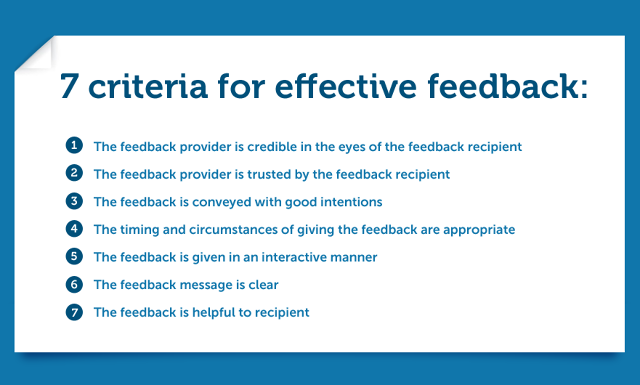

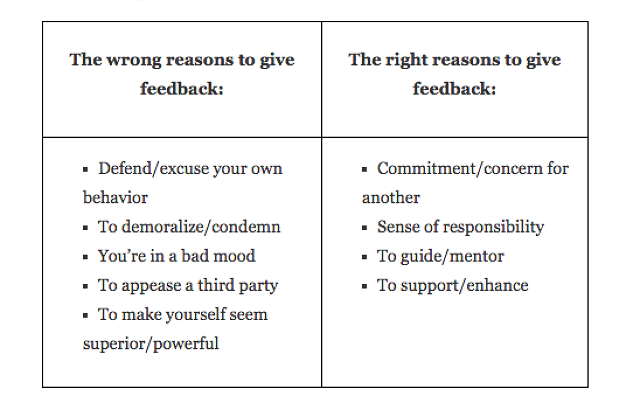

Reflect

on your purpose

The

most important step is to make sure that your potential feedback is

coming from the right place. Here’s a list of some of the

main motivating factors

behind

offering up feedback.

"When

we have difficult feedback to give, we enter the discussion uneasily,

and this pushes us to the side of fear and judgment, where we believe

we know what is wrong with the other person and how we can fix him,"

writes Frederic Laloux in his book Reinventing

Organizations.

"If we are mindful, we can come to such discussions from a place

of care. When we do, we can enter into beautiful moments of inquiry,

where we have no easy answers but can help the colleague assess

himself more truthfully."

Focus

on the behavior, not the person

After

entering the conversation with the best intentions, a next guideline

is to separate behavior or actions from the person you’re speaking

to.

Focusing

the criticism on just the situation you want to address—on what

someone does or says, rather than the individual themselves—separates

the problematic situation from the person’s identity, allowing them

to focus on what you’re saying without feeling personally

confronted.

Lead

with questions

Starting

off your feedback with a few questions can help the other person feel

like an equal part in the conversation as you discuss the challenge

together.

Neal

Ashkanasy, a professor of management at the University

of Queensland in Australia, shared

with Psychology

Today the

story of overcoming a tough feedback challenge—firing an

assistant—with questions:

Ashkanasy began by asking her how she thought she was doing. That lead-in gives the recipient "joint ownership" of the conversation, he says. Ashkanasy also pointed to other jobs that would better match the skills of his soon-to-be-ex employee. That promise of belonging helped relieve her anxiety about being cast out of the group she already knew.

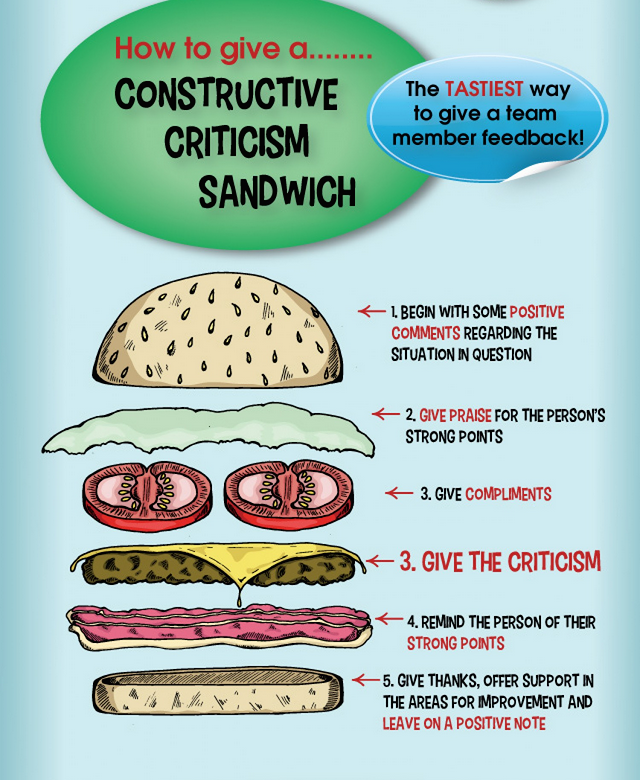

Inject

positivity: The modified ‘criticism sandwich’

"Sandwich every bit of criticism between two heavy layers of praise." – Mary Kay Ash

One

well known strategy for feedback is the "criticism sandwich,"

popularized by the above quote from cosmetics maven Mary Kay Ash. In

the sandwich, you begin with praise, address the problem, and follow

up with more praise.

In

fact, the more of the conversation you can frame positively, the more

likely your recipient is to be in the right frame of mind to make the

change you’re looking for.

The

blog Zen

Habits offers up some phrases to try to

inject more positivity into your feedback, like: "I’d love it

if …" or "I think you’d do a great job with …"

or "One thing that could make this even better is …"

Follow

the Rosenberg method: Observations, feelings, needs, requests

In

his exploration of the next phase of working together, Reinventing

Organizations,

Frederic Laloux explores some of the world’s most highly evolved

workplaces. One of the cultural elements common to all of them is the

the ability to treat feedback as a gift rather than a curse.

As

Laloux puts it, "feedback and respectful confrontation are gifts

we share to help one another grow."

Many

of these organizations use the Rosenberg

Nonviolent Communication method, pictured

here, to deliver feedback.

This

method provides a simple and predictable framework that takes some of

the volatility out of giving and receiving feedback.

THE BEST WAY TO PREPARE FOR AND RECEIVE CRITICISM

So

now we know some strategies for offering feedback with an open heart

and mind. How about for receiving it?

Ask

for feedback often

The

best strategy for being caught off guard by negative feedback? Make

sure you invite feedback often, especially from those you trust.

You’ll be better able to see any challenges ahead of time, and

you’ll gain experience in responding positively to feedback.

You

can begin by preparing some open-ended questions for those who know

you well and can speak with confidence about your work. Here are some

great example

questions:

- If you had to make two suggestions for improving my work, what would they be?

- How could I handle my projects more effectively?

- What could I do to make your job easier?

- How could I do a better job of following through on commitments?

- If you were in my position, what would you do to show people more appreciation?

- When do I need to involve other people in my decisions?

- How could I do a better job of prioritizing my activities?

Ask

for time to reflect on what you’ve heard, one element at a time

When

receiving feedback, it might be tempting to become defensive or

"explain away" the criticism. Instead, let the other person

finish completely and try to listen deeply. Then ask questions and

reflect thoughtfully on what you’ve heard.

Stanford

Professor Nass

says that

most people can take in only one critical comment at a time.

"I

have stopped people and told them, ‘Let me think about this.’ I’m

willing to hear more criticism but not all at one time."

So

if you need some time to reflect on multiple points of feedback,

don’t be afraid to say so.

Cultivate

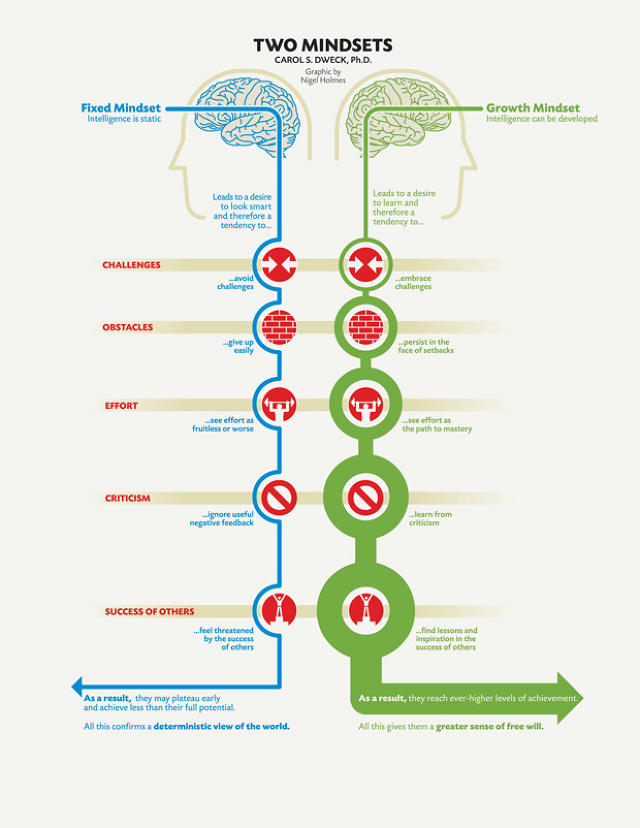

a growth mindset

While

some of us have a hard time hearing negative feedback, there are

those who thrive on it. This group has what’s known as a growth

mindset. They focus on their ability to change and grow—as opposed

to those with a fixed mindset—and are able to see feedback as an

opportunity for improvement.

You

can learn more about how to develop a growth mindset here.

Take

credit for your mistakes and grow

It’s

easy to take credit for our successes, but failure is something we

don’t like to admit to. For example, we’re more likely to blame

failure on external factors than our own shortcomings.

But

lately, the idea of embracing failure has emerged, and it’s a great

mindset for making the most of feedback.

"Continual

experimentation is the new normal," says business psychologist

Karissa Thacker. "With risk comes failure. You cannot elevate

the level of risk taking without helping people make sense of

failure, and to some extent, feel safe with failure."

Take

a page from the "embracing failure" movement and treasure

the opportunities you’re given to improve and grow.

HOW WE GIVE AND RECEIVE FEEDBACK

As

with many of the things we do at Buffer, the way we give and receive

feedback is a continuous work in progress as we experiment, learn and

grow.

Previously,

the feedback process was more or less formalized in a process we call

the

mastermind.Each

team member would meet with a team leader every two weeks in a format

with the following structure:

- 10 minutes to share and celebrate your achievements

- 40 minutes to discuss your current top challenges

- 10 minutes for the team lead to share feedback

- 10 minutes to give feedback to the team lead

This

process had a few really good things going for it: Feedback was a

regular, scheduled part of our discussions, which removed a lot of

the fear that can surround it; and feedback always went both ways,

which made it feel like a sharing process between two equals.

These

days, masterminds happen weekly between peers and we’ve moved away

from the formalized feedback section altogether as we strive for a

more holacratic, less top-down way of working together.

But

feedback is still an important part of the Buffer journey, and it is

offered and received freely by any of us at any time it is

applicable.

Since

feedback often can be sensitive and personal, it tends to be one of

the only elements we exempt from our policy of radical transparency.

It most often takes the form of one-on-one Hipchat messages, emails

or Sqwiggle conversations.

Our

values guide the feedback process

Buffer’s

10 core values are

our guide to offering and receiving feedback with joy instead of

anxiety.

Looking

at our value of positivity through a lens of feedback, I see lots of

great instruction on offering constructive criticism, including

focusing on the situation instead of the person and offering as much

appreciation as feedback.

Since

we each take on this goal of positivity, it’s very easy to assume

the best of the person offering their feedback to you and that their

intent is positive.

Additionally,

our value of gratitude means that we each focus on being thankful for

the feedback as an opportunity to improve in a particular area.

Finally,

our value of self-improvement means we have a framework for taking

feedback and acting on it in a way that moves us forward.

Although

feedback isn’t generally made public to the whole team, it’s not

uncommon for team members to share feedback they’ve received and

the changes they’re making as a result in pair calls or

masterminds.

BY COURTNEY

SEITER

http://www.fastcompany.com/3039412/the-art-science-to-giving-and-receiving-criticism-at-work?utm_source=mailchimp&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=fast-company-daily-newsletter&position=featured&partner=newsletter&campaign_date=12102014

No comments:

Post a Comment